Title: Beowulf

Author: Anonymous

Written: 750 CE

Pages: 213 Pages

Structure: An epic poem consisting of 3,182 lines

Beowulf is a wonderfully strange book.

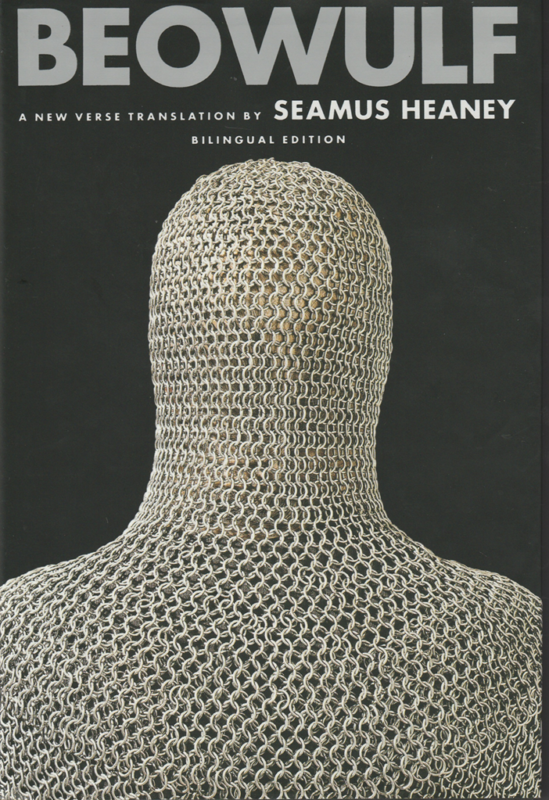

I read the Seamus Heaney translation which shows the original Old English on one page, and the modern English translation on the other. This is a fun way to try to learn a little Anglo Saxon. Heaney’s translation appears to prioritize poetic faithfulness over word-for-word accuracy, which I enjoyed.

The original text was written by an anonymous author, probably in the 8th century, in Old English, or Anglo-Saxon – a language which looks more like Icelandic than modern English.

It retells the story of a hero from Southern Sweden (Geatland) who lived during the 5th century and probably worshiped Norse gods like Óðinn (Odin) and Þórr (Thor).

The story was passed down orally by bards, and includes earlier songs of heroes such as Finn and Sigemund.

If you read the story simplistically, it’s about how Beowulf and his band of soldiers sail from Geatland to rescue the Danes from two monsters, then return home with a hoard of treasure. Beowulf rules for fifty happy years, then eventually has to fight and kill a dragon, but is, himself, killed in the process.

But the story is way more than that.

The poetry is beautiful. We see “kennings”, or descriptions of everyday things using poetic language. So the sea is the “whale’s road” or the “gannet’s bath”. A human body is a “bone house”. A king is a “ring giver”. And a lifetime is “borrowed days”.

Life was brutal and short in these days, but the philosophy was powerful, reminding listeners to live well:

“But death is not easily escaped from by anyone;

nor can any man, through courage alone,

avoid it for a time or suffer nothing of it,”

Here’s some Anglo-Saxon : “Nū is þīnes mægnes blæd āne hwīle.”

Roughly translated it means “Now the bloom of your strength is but for a little while.”

Some more quotes:

Anglo-Saxon: “Gædth ā wyrd swā hīo scel!”

Translation: “Fate always goes as she must!”

Anglo-Saxon: “wyrd ungemete nēah”

Translation: “Fate was unknowable but near (or certain)”

Between us and Beowulf is the narrator / author, who is a Christian. At the start of his story, the narrator admits that his protagonists “do not know the Lord”. But he embellishes his story to describe how his heroes pray to God and give thanks to him.

The author takes what is obviously a Norse oral tale of heroism, and embellishes it with his own Christian symbols. I imagined a scribe or monk, writing on parchment by the light of a candle, recalling the story as he had heard it, and trying to understand it by casting it in his own pantheon. (We all do this when we retell stories).

The result is a work of literature which captures an inflection point in our history. The old gods had passed away, the people had created new gods. And so we listen to an 8th century poet in England trying to describe life and death in 5th century Sweden and Denmark.

It’s wonderful. Like Beowulf, our “wyrd” or “fate” is impossible to know, but it is certain. What better thing could we do than live well?

One final easter-egg. Beowulf was brought to greater public awareness by JRR Tolkein in his 1936 paper “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics”. The story inspired him to write his own heroic epic The Lord of the Rings. At line 2345 in the story, Beowulf is anticipating his battle with the dragon, he knows he will probably die, and the author describes him with the kenning “hringa fengel”.

“Hringa Fengel” in Anglo-Saxon is translated as “Lord of Rings”.