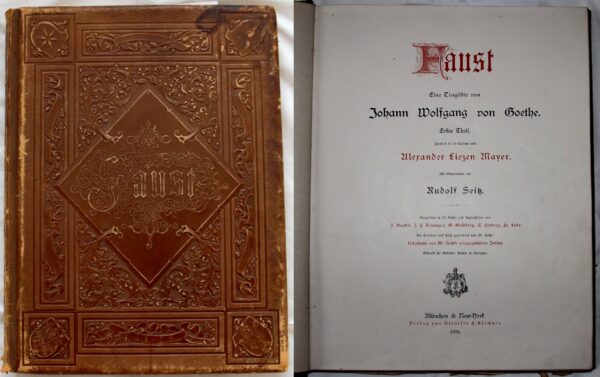

Title: Faust. A Tragedy

Author: Johann von Goethe

Written: 1772 – 1831

Translator: Walter Kaufmann

Pages: 503 Pages

Structure: A play in two parts, 12,111 lines

“Faust” is an old German legend that has been retold many times by many different authors. It is based on the life of Dr Johann Faustus, a German magician and astrologer who lived in the fifteenth century.

We have been fascinated with his story for centuries. His legend has inspired music by Beethoven, Schubert, Verdi, Wagner, Mendelssohn, and many others. It has inspired literature by Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Mann, Oscar Wilde, Louisa M Alcott, Lord Byron, and Robert Louis Stevenson, to name a few. But the work that stands our among all these is the play “Faust” by Johann von Goethe, considered by many to be the greatest work of German literature.

Goethe spent decades writing his version of Faust. He began writing when he was 23 years old, and didn’t publish the final part of the story until he was 82 years old in the final year of his life. This was his life’s work.

I read the Walter Kaufmann translation, which presents the original German text on the left-hand page, and a modern translation on the other page. This worked well for me.

Setting the “Stage”

The story cunningly opens with a Theatre Director speaking with his Poet and Clown about an upcoming play – the one we’re about to watch. They discuss the shallowness and distracted nature of their audience. The Poet laments how “Glitter is coined to meet the moment’s rage” – how easy it is to create meaningless entertainment to suit short-term tastes. The Clown simply wants to enchant the audience and tells the poet to “Give us a play with such emotion! Reach into life, it is a teeming ocean!” The Director wants success and fortune. “To please crowds is what I desire most… The more you can enact before their eyes, the greater is your popular acclaim.”

Goethe then moves us into Heaven where a discussion takes place between God, the Angels and the demon Mephistopheles. As with the opening scenes of the biblical book of Job, Mephisto criticizes the whimsical nature of Humanity, and makes a wager with God that he will be able to lead Faust astray. God agrees to the bet, knowing in advance (of course) that he’ll win it, and lets us in on a little secret: “Man errs as long as he will strive”. In other words, humans make mistakes because of the simple fact that they yearn for more. It’s inevitable. It’s not morally fatal. God predicts:

“A good man in his darkling aspiration

Remembers the right road throughtout his quest”

So right at the start, we’re told that we’re watching a play that takes into account that we (the audience) are preoccupied with inconsequential things, and that the higher forces of the universe are toying with us to see what we’ll do. It’s all a play – and we’re both the audience and the actors.

The “Play”

And so the story of Faust begins:

What do we yearn for most? What would drive a person to make a pact with the Devil? How would that decision change them? And finally, what is a “good” person? Goethe poses all these questions by showing us the life of a brilliant academic who yearns for knowledge. He’s not content with what he has learned in his years of study – he wants to know more.

“I have, alas, studied philosophy,

Jurisprudence and medicine, too,

And, worst of all, theology

With keen endeavor, through and through-

And here I am, for all my lore,

The wretched fool I was before.

Called Master of Arts, and Doctor to boot,

For ten years almost I confute

And up and down, wherever it goes,

I drag my students by the nose-

And see that for all our science and art

We can know nothing. It burns my heart.”

In his craving for truth, Faust searches for knowledge in unconventional places, makes some unsuccessful attempts at exploring the occult, and eventually finds himself on the verge of ending his life. This eventually leads to an encounter with a strange black dog, who is actually Mephistopheles in disguise. These days we refer to depression as “the black dog”. The similarity is not coincidence. The black dog personifies internal despair, inner darkness. It is persistent, intimate, and intrusive. Faust’s inner anguish is taking form.

The dog transforms into the demon Mephistopheles, who has a philosophical discussion with Faust. Faust discovers that the pentagram he inscribed on the floor has trapped the demon, and comes up with the idea of making a bargain with him. The idea of the pact with the Devil doesn’t come from Mephistopheles, but from Faust himself. He’s complicit in this deal – not merely a duped victim. As with most scams, the victim sees an offer that is too good to be true, and seeks to take advantage of it.

The twist is that Mephisto thinks that he can ensnare Faust by offering him unlimited pleasure, and that in fulling quenching that hunger, he’ll win Faust’s soul. But Faust doesn’t want pleasure. He wants to be “cured from the craving to know all.”

At first, the demon is successful. He administers a potion to Faust that causes him to find all women irresistible, and uses this poisoned desire to trick Faust into pursuing Gretchen, getting her pregnant, slaying her brother, and poisoning her mother. Gretchen is utterly destroyed and imprisoned for the murder of her child, and a despairing Faust is unable to save her.

The “Twist”

The second part of the story shows the transformation of Faust, and why he is redeemable despite his horrible errors. Faust moves into the world, and becomes a figure of action. Faust wants to make a contribution to society through a huge land reclamation project. He’s not interested in what the world can give him, but in what sort of world he can build for future generations using his power. In this environment, Mephistopheles is reduced from being a corrupting demon to becoming a clever administrator.

Towards the end of his long life, Faust is tested by four primordial spirits: Want, Guilt, Care and Need. Three of these spirits are unable to touch him because his life is not focused on inner needs and wants.

Faust no longer feels incomplete, so “Want” has no effect on him.

He does not dwell on himself or on self-condemnation, so “Guilt” cannot touch him.

He does not worry about personal desires, so “Need” is ineffective.

The only spirit that has any effect is “Care”. She reminds him of his own mortality and limitations, and strikes him blind. But he is undaunted:

“Deep night now seems to fall more deeply still,

Yet inside me there shines a brilliant light;

What have I thought, I hasten to fulfill:

The master’s word alone has real might.

Up from your straw, my servants! Every man!

Let happy eyes behold my daring plan.”

Faust realizes his own mortality, and is resolved to “make the grandest dream come true.”

Faust dies, entirely focused on using his power to build a better world. Mephistopheles is uneasy, and realizes something is amiss:

“Fie!

No pleasure sated him, no great bestowment,

He reeled from form to form, it did not last;

The final, wretched, empty moment,

The poor man wishes to hold fast.

He sturdily resisted all my toil;

Time conquers, old he lies here on the soil.

The clock has stopped-“

And despite Mephisto’s desperate attempts to claim his soul, Faust is redeemed, and the angels bear his soul away.

We end up seeing ourselves in Faust’s story – in his drive for more, in his stupid mistakes, in his desire for a better world. By some work of sublime artistic magic, Goethe has transformed us from reader at first, then to audience, and finally to actor. We are Faust. We are looking in the mirror.

Themes

One idea which continually recurs in the play is “striving”. It’s described as an inevitable human attribute by God at the start of the story. Throughout the play Faust continually refers to his own striving for something more. At the end, as the angels carry Faust away they say “Who ever strives with all his power, we are allowed to save.”

Goethe seems to be saying that this “strebend” is part of being human. It’s the thing which causes us anguish, makes us fall, but eventually redeems us. It’s not that we believe the right things, but that we strive for something better than what we see.

That striving can be temporarily corrupted – this has always happened in human affairs, but the human desire for truth and justice eventually transcends the manipulation that is imposed upon us by the malignant creatures that do exist in our world..

Faust is a great work. It’s odd that I read it immediately after Don Quixote. Both men long for a better world. Both men live tortured lives. Both men are eventually redeemed.

Perhaps the universe is trying to tell me something!