Title: The Lord of the Rings

Author: J.R.R.Tolkien

Published: 1955

Pages: 1567 Pages

Structure: 6 “Books” each containing between 9 to 12 chapters, plus 6 appendices and 3 indexes, published in 3 volumes

Tolkien’s “The Lord of the Rings” (LOTR) is a masterpiece – one of the greatest works of literature of the twentieth century. I have never read a book with so much depth in its world, and such broad and majestic themes.

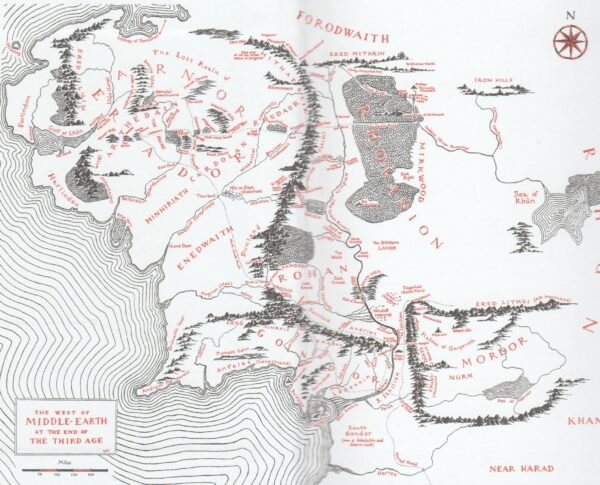

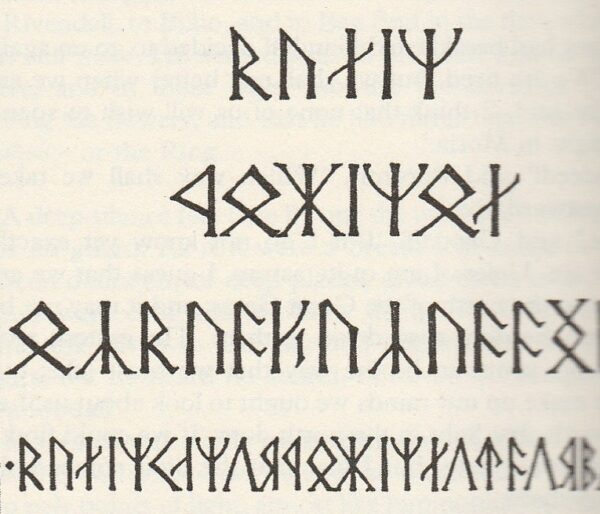

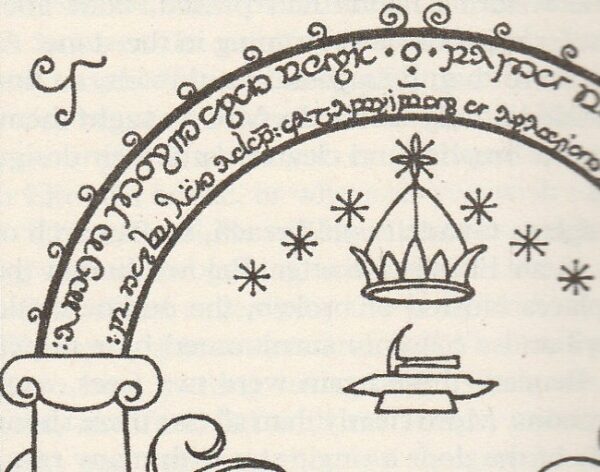

Tolkien didn’t just write a story, he created an entire world. He invented languages and alphabets, crafted creation myths and legends which are referred to in the story, and embellished the book with some of the most beautiful poetry you can find. And he wraps all of that around the compelling theme of the battle between good and evil, self-sacrifice, perseverance, and friendship.

The result is majestic iceberg, with most of its reality hidden from sight. What is visible is sublime, but it only exists because of the vast majority of the world he created beforehand to which he only alludes in the story.

As with all great epics, Tolkien uses “in media res” in LOTR. The story starts in the middle of things. There has been an epic struggle between Good and Evil since the before the foundation of Middle Earth. Morgoth wanted to dominate or destroy the world. He was defeated, but his servant, Sauron continued the fight and forged the One Ring to control the world and eventually overthrow it.

That previous paragraph covered a time span of thousands of years, and another huge book. Such is the mythic craft of the author.

By some strange twist of fate (as always happens in epics), the One Ring is lost, and eventually finds its way into the hands of Frodo, the son of Drogo and nephew to the famous Bilbo Baggins. Oddly, the One Ring feels like a character in this story, not just a thing. It has a will of its own and affects those near it.

Most people, given the chance, would attempt to wield the One Ring, and use its power for themselves. But those who did (Isildur, Smeagol / Gollum) were changed into shadows of themselves.

Sauron, who wants his ring back so that he can rule the world, expects that whoever finds the ring will wield it. It never enters his head that someone would shun the power of the ring and destroy it – which is precisely what Frodo and his companions decide to do.

I love the ethics of this idea. All of us have different ideas of what is “evil” in this world. But Tolkien suggests that if you want to oppose evil, you don’t use the same tactics as your opponents. You can’t defeat the abusers of power by abusing power yourself. “Good” sees the world differently from “Evil”. It behaves differently, and ultimately can never be understood by Evil. As the writer of the fourth gospel wrote in its first chapter “the light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not comprehend it.”

This is understandable considering the Tolkien’s environment while writing his tale – the ongoing fight against totalitarianism and fascism during the First and Second World Wars.

This theme of self-sacrifice is repeated often in the story. The most notable and iconic scene in the first volume (The Fellowship of the Ring) shows us Gandalf the Grey standing alone on the Bridge of Khazad-dûm facing the gruesome Balrog – a primordial demon.

“You shall not pass!”

Those words still give me goosebumps when I see them.

Gandalf risks his life in order to allow his companions to escape the Mines of Moria. As a result, he is dragged down into the mirky depths by the monster while his friends flee the cave.

Towards the end of the book (in The Return of the King), Gandalf and Aragorn agree to risk their own lives and an entire army, with little chance of victory, simply to give Frodo a better chance of destroying the ring.

“We must walk open-eyed into that trap, with courage, but small hope for ourselves. For, my lords, it may well prove that we ourselves shall perish utterly in a black battle far from the living lands. So that even if Barad-dûr be thrown down, we shall not live to see a new age. But this, I deem, is our duty. And better so that to perish nonetheless – as we surely shall, if we sit here – and know as we die that no new age shall be.”

In parallel with these epic themes, Tolkien bejewels his story with wonderful poetry in a variety of different forms and languages.

Bilbo’s poem:

The Road goes ever on and on

Down from the door where it began.

Now far ahead the Road has gone,

And I must follow, if I can,

Pursuing it with weary feet…

The song of the High Elves:

…Gilthoniel! O Elbereth!

Clear are thy eyes and bright thy breath!

Snow-white! Snow-white! We sing to thee

In a far land beyond the Sea…

Samwise Gamgee’s song in the “Prancing Pony” as he danced on the tables:

There is an inn, a merry old inn

beneath an old grey hill,

And there they brew a beer so brown

That the Man in the Moon himself came down

one night to drink his fill…

The Elvish tale Tinúviel:

The leaves were long, the grass was green,

The hemlock-umbels tall and fair,

And in the glade a light was seen

Of stars in shadow shimmering.

Tinúviel was dancing there

To music of a pipe unseen,

And light of stars was in her hair,

And in her raiment glimmering…

The poem which delighted me most was the song of the Mounds of Mundburg – a song of the Riders of Rohan. Tolkien wrote this using the same alliterative style used in Beowulf – it’s an Anglo-Saxon poetic form where there is no rhyme or predominant rhythm. He uses alliteration instead (Heard Horns Hills, Swords, Shining, South, Steeds, Striding, Stoningland, etc)

We heard of the horns in the hills ringing,

the swords shining in the South-kingdom.

Steeds went striding to the Stoningland

as wind in the morning. War was kindled.

There Théoden fell, Thengling mighty,

to his golden halls and green pastures

in the Northern fields never returning,

high lord of the host. Harding and Guthláf,

Dúnhere and Déorwine, doughty Grimbold,

For those in the know, “Lord of Rings” is a term used in Beowulf. That’s exactly what the Anglo-Saxon words “Hringa Fengel” mean, when the author of Beowulf describes the hero preparing to do battle with the dragon.

Similarly “Middle Earth” is borrowed from Beowulf’s “Middan geard”, which is from Old Norse “Miðgarðr” – both which mean “Middle Earth” – the place where humans live, suspended in the “middle” between Heaven and the Depths of the Void.

I was blown away when I saw the mastery of the author – the command he had of language, and the way he wielded it to craft such an immersive and believable world. I have never seen another author even come close to this level of craftsmanship.

The Lord of the Rings is unique. It is a long book (over 1,500 pages) and is best read slowly – especially the poetry. Yes, Peter Jackson’s films which are based on the book are excellent. But the book is deeper, more detailed, and more enjoyable.

I am so glad that I read it.