Title: The Odyssey

Author: Homer

Written: circa 700 BCE

Translator: Emily Wilson, 2018

Pages: 582

Structure: 24 “books”, each about 400 to 900 lines (10 to 20 pages) long.

The Odyssey is a timeless tale about trying to return home. After fighting in a brutal war for a decade a brilliant but battered man, Odysseus, finds himself continually thwarted by misfortune for a second decade while he tries to come back to his family. At the same time his wife, Penelope, is harassed daily by suitors who try to convince her that her husband is dead and that she should marry one of them.

“when a man is far from home,

living abroad, there is no sweeter thing

than his own native land and family.”

9:35-37

The story is compelling – I’ve read it twice, and couldn’t put it down on both occasions. But experiencing The Odyssey is more than reading a gripping story. There is something magical about how Homer crafted this tale that make it one of the greatest works of literature.

Like all good epics, Homer starts his story in the middle of everything. This isn’t a “once upon a time” fairy tale. On the first page urgent things are happening in many places simultaneously. Gods are arguing and intervening in the affairs of humans; a man is imprisoned on an island with no hope of escape; interlopers are behaving atrociously in that man’s home while he is absent.

The story is multi-layered. We don’t just get a flat linear account of how things happened. This account unfolds before us from multiple perspectives, with flashbacks, stories within stories, and even fake stories. We get to see gods pretending to be humans, inventing their own backstories, and manipulating humans. We see Odysseus recounting the early years of his voyage while his audience listens, mesmerized, until dawn. And we hear as Odysseus invents a false history as he pretends to be an old soldier fallen on hard times whiles tries to sneak into his old home without being discovered by his enemies.

In Book 7, Odysseus finds himself washed ashore on the island of Phaecia, and asks a young girl for directions to the palace. Unbeknownst to him, the young girl is the goddess Athena in disguise. I think this account of the interaction is delightful:

With twinkling eyes

the goddess answered, “Mr. Foreigner,

I will take you to where you want to go.

The king lives near my father’s home…The goddess led him there.

He followed closely in her skipping steps.

The seafaring Phaeacians did not see him

as he passed through the town, since that great goddess,

pigtailed Athena, in her care for him

made him invisible with magic mist.

(7:27-42)

I laughed when I read “pigtailed Athena” and wondered if the translator had taken liberty with the translation. Some of the older translations (such as Butler or Pope) don’t present Athena so colorfully. So I had a look at the original Greek (warning, I am not a scholar of ancient Greek).

Homer says “εὐπλόκαμος Ἀθήνη” which literally means “Athena with the beautiful coils / braids of hair.” Butler’s translation completely ignores it and just says “the great goddess Athene in her goodwill”.

This helped me realize that Odysseus is not the only protagonist in this story. Athena is just as important. It’s her intervention that ensures the hero’s eventual success.

One of the most moving scenes is in Book 8 where Odysseus is feasting with King Alcinuous. He has not yet revealed his identity, and the blind bard Demodocus sings to entertain them.

Demodocus regales his audience with a song about the quarrel between Achilles and Odysseus during the Trojan war. No one present, except Odysseus, realizes that the man in the song is actually seated with them listening to it. Odysseus is moved to tears by the song, and covers his face with his robe so that the audience can’t see how upset he is.

I see Demodocus as almost a cameo appearance by Homer. The story says that the Muse caused his blindness. “She gave him two gifts, good and bad: she took his sight away, but gave sweet song.”. Tradition says that Homer was blind. In a way, Homer seems to be saying that he’s telling us a story about ourselves, and we’re in the audience listening and being moved to tears because it feels so familiar.

Eventually, Odysseus reveals who he is, and tells his story to the assembled crowd. In an unusual twist, the narrative switches from being in the third person, to being in the first person as Odysseus tells his tale:

“The Cloud Lord Zeus hurled North Wind at our ships,

a terrible typhoon, and covered up

the sea and earth with fog. Night fell from heaven

and seized us and our ships keeled over sideways;

the sails were ripped three times by blasting wind.

Scared for our lives, we hoisted down the sails

and rowed with all our might towards the shore.”

9:67-74

The language is powerfully evocative, as you’d expect in a Homeric epic. The audience is transfixed. They can’t get enough of his story. It’s a tale of man-eating giants, mountainous seas, witches that can turn men into pigs, and a goddess who keeps him imprisoned as a sex-slave for seven years.

Another powerful device Homer uses in the story is the flashback. Someone touches something, and immediately you have a scene describing the history of that thing.

Here’s a scene where Eurycleia the servant washes Odysseus’ legs, but he is in disguise at the time – no one knows who he is. Suddenly she touches a scar, and has a flashback as she realizes who she is touching:

Suddenly, she felt

the scar. A white-tusked boar had wounded him

on Mount Parnassus long ago. He went there

with his maternal cousins and grandfather,

noble Autolycus, who was the best

of all mankind at telling lies and stealing.

Hermes gave him this talent to reward him

for burning many offerings to him.

Much earlier, Autolycus had gone

to Ithaca to see his daughter’s baby,

and Eurycleia put the newborn child

on his grandfather’s lap and said, “Now name

your grandson-this much-wanted baby boy.”…

19:394-406

Similarly when Penelope goes to the armory to fetch a bow and arrow for use in an archery competition:

Then with her slaves she walked

down to the storeroom where the master kept

his treasure: gold and bronze and well-wrought iron.

The curving bow and deadly arrows lay there.

given by Iphitus. Eurytus son,

the godlike man he happened to befriend

at wise Ortilochus house, far off

in Lacedaemon, in Messenia.

Odysseus had gone to claim a debt-

some people of Messenia had come

in rowing boats and poached three hundred sheep.

21:12-19

It feels like every item has its own magical story. We examine something and a trove of memories flood us. It’s the sort of tactic that filmmakers employ to deepen their stories. But this dark art was invented by Homer long before movies.

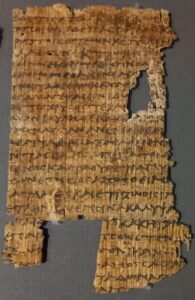

This epic poem was originally performed orally over several nights.

Imagine a singer (aoidos) or a reciter of poetry (rhapsode) reciting the poem to us verbally, from memory, in ancient Greece. Not delicately, but boldly with actions, loud intonations, and dramatic voices. The audience would have been enchanted. This would have been better than going to the movies, or reading a book.

Can you imagine it?

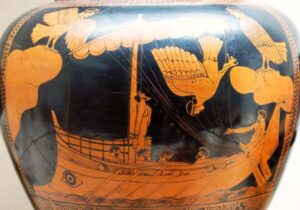

By Siren Painter (eponymous vase) – Jastrow (2006), Public Domain, Link

Emily Wilson’s translation is easy to understand, entertaining, and (I think) faithful to the spirit of the story. If you’re going to buy a translation, I think this is one of the best.

While not maligning the seventeenth century poetry of Alexaner Pope’s translation, or the grand Victorian prose of Samuel Butler, I think Wilson’s translation is more relevant to a twenty-first century reader. Homer didn’t speak seventeenth century English. Victorian prose was foreign to him. His stories weren’t meant to be treated like reading sacred scriptures. They’re entertainment. They were meant to be enjoyed by an audience of his peers from various walks of life. Wilson’s translation makes that possible.

And at the same time, Wilson’s translation uncovers the agency of the heroines of the story, Athena and Peneleope. Archaic english has often clouded their clever actions and mischievous attitudes.

This is one of the greatest works of literature in the western canon.

Please read it.

11 ⁄ 12

More details

Ulysses and Telemachus kill Penelope’s Suitors by Thomas Degeorge (1812)

By VladoubidoOo – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, Link